Tests

Cinematography for Directors: Focal Length (Part 1)

On 14, Sep 2013 | 4 Comments | In Tests, Instructional | By Colton Davie

Like the other departments of film production, cinematography is a specialized field. As cinematographers, we are required to fully grasp and utilize concepts and tools that may never be completely understood by other members of production. For instance, a director may never need to know how to read a waveform monitor, or the difference between griffolyn and ultrabounce. However, the choices the cinematographer makes regarding exposure, or his choice of bounce, or the myriad of other technical decisions ultimately have narrative and emotional impact on the film. Therefore, it is wise for directors to have a basic grasp of cinematographic techniques—as well as the other aspects like production design, sound, and editing—so that they can confidently and deliberately work with their collaborators to craft their vision.

With that in mind, I’ve set out to write a series of articles on foundational concepts of cinematography, for directors. I intend to approach these concepts from a story perspective as opposed to an overly technical one. My goal is to help new directors get up to speed, or provide a refresher for those that may have more experience, so that they can more effectively communicate with their cinematographer and better craft a film that is in line with their vision.

The Lens

One of the most foundational aspects of cinematography is the lens. The lens is the eye through which everything that appears in front of the camera, the acting, the set design, the lighting, is seen. As such, it is probably the aspect of cinematography about which the director should be most knowledgeable, particularly in regards to focal length. The choice of focal length for a shot is almost always a joint decision between the director and cinematographer, if not dictated by the director. This choice both sets the frame of the shot, what is included and what is excluded, as well as the depth of the shot, the relationship between and visual components of the shot and the sense of 3-dimensional space.

Without getting too technical, focal length can be defined as the distance between the optical center of the lens and the image plane (the sensor or film) when the lens is focused at infinity. Focal length is typically measured in millimeters, and is the primary defining trait of a lens. On super 35mm film, or an equivalent-sized sensor, such as on the ALEXA, a 50mm lens is typically considered a “normal lens.” This is because the perspective of a 50mm lens closely resembles that of the human eye. Lenses with focal lengths shorter than 50mm are considered wide lenses, and those with longer focal lengths are called long lenses.

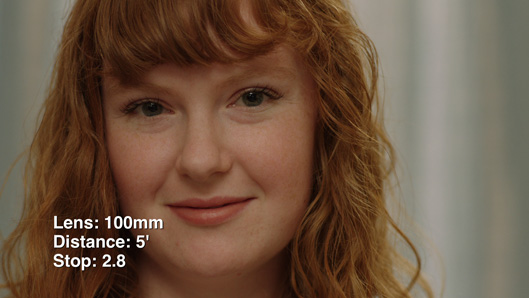

Watch the following video to see the effects of focal length in action, then continue reading for further explanation. This demonstration was shot on the ALEXA with my set of Zeiss Standard Speeds, which includes six lenses, a 16mm, 24mm, 32mm, 50mm, 85mm, and 100mm. Thanks to the camera-inquisitive directors Aaron Wright and Bryce McGuire for helping out, and Kelly for modeling her new bangs.

Framing

As I mentioned before, focal length directly affects the framing of the shot. This is demonstrated in section 1 of the video. In these shots the distance between the camera and the subject remains constant. Only the focal length changes between shots.

As you can see, wide lenses have a wide angle-of-view, revealing a lot of the subject and her surroundings.

However, without moving the camera, as we go to longer and longer lenses, the angle-of-view becomes narrower, making the subject appear larger in frame and revealing less of her surroundings.

This is very basic, but the storytelling implications are significant. A wide angle shot in which the subject is very small, and the emphasis is on her surroundings has a very different narrative, informational, and emotional impact than a long lens shot that brings all of the attention directly to the subject’s face.

Using different focal lengths can also add interest and variety to a scene, providing additional coverage and options for the edit. A very simple and often used technique is to cover a character in a medium shot, say with a 32mm, then swing lenses to something like an 85mm to cover her close up.

Depth

Where things can really get interesting is when you start to consider the impact that focal length has on the depth or apparent perspective of a shot. In section 2A of the video, we framed for a head and shoulders close up. Each time we changed lenses, we moved the camera forward or backward as necessary so that the framing of the subject remained the same. We did the same thing in section 2B, but framed for a full-body shot instead.

Even though the subject is framed the same way, you can feel a pretty big difference between, for example, the 24mm lens and the 100mm.

As I said before, 50mm is considered normal because it gives the most natural sense of perspective. Personally, I feel like a slightly wider lens, like the 32mm is closer to how my eyes see the world. Either way this middle range is definitely the most “normal” feeling in terms of perspective.

The wide lenses, however, seem to exaggerate perspective. The apparent distance between objects as they extend away from the camera seems to be greater than normal, and objects in the foreground appear larger than normal in relation to objects in the background. This contributes to a strong sense of 3-dimensional depth.

On the other had, the long lenses appear to compress perspective. The apparent distance between objects as they extend away from the lens seems to be smaller than normal, and objects in the foreground appear to be smaller than normal in relation to objects in the background. This tends to result in the feeling of compressed, almost 2-dimentional space, with less sense of depth.

The effect focal length has on apparent depth means that the lens you choose can have a great impact on the intimacy and presence of a shot. Shooting a close up with a wide lens, such as a 24mm, gives the sensation of being in the character’s space. In practical terms you actually are placing the camera right there in the middle of the action, and the audience can feel that. Conversely, a long lens, like a 100mm or longer, can feel voyeuristic and distant. Even though the subject may be large in the frame, you can sense the space between her and the camera, which may feel cold or detached.

So now then…

The better you get a feel for these concepts, the more effectively you should be able to use them for emotional effect.

An exciting thing about the choice of focal length, and many other creative and technical choices, is that there is no concrete formula relating that choice to emotional impact. There are tendencies and conventions, but those can quickly be subverted.

For example, wide lenses may generally give a sense of presence, and being there with the characters, but consider the films of Stanley Kubrick. He loved really wide lenses, yet his films are generally ice cold, much more observational than intimate. This is because his choices of focal length are in the context of his choices regarding the script, the blocking of the actors, the stark compositions, the deliberate camera moves, etc. It’s not that these choices cancel out the effect of his wide lenses, but that these choices build upon each other to create a situation where the wide lenses actually contribute to that cold, observational feeling.

As you learn to deliberately apply the concepts of focal length, don’t get hung up on one choice meaning this or another choice meaning that. Instead, cultivate a sense what different lenses look like in various situations, and how those lenses interact with the many other choices that must be made. Then, working with your cinematographer, your production designer, your talent, and the rest of the team, you can craft a film that effectively communicates the ideas and emotions you intend to communicate.

Practical Issues

Before we go, I want to point out a few of the practical ramifications of different focal lengths. They may be obvious, but I think they are worth noting.

- Wide lenses reveal much more of the set. When using wide lenses, be prepared to dress large areas, or be careful that you are not seeing off the set. Also, lighting and sound recording can be tricky with very wide lenses, because it can be difficult to hide lights or the boom mic, as you can see in section 1B.

- In section 2A, it became a challenge to get the camera physically close enough to the subject to achieve the proper framing. On the 16mm lens, the camera was less than 2′ from her face. When shooting coverage this close, the talent often has to cheat her eyelines as the camera can very well be blocking her view of the other actor. Also, when this close the cinematographer must be aware of the camera possibly interfering with the lighting.

- You notice in section 2B that we went outside. This is because in order to get the full shot framing with the 100mm lens, the camera had to be 60′ away from the subject. There simply wasn’t enough room indoors. This leads to the following point:

- Sometimes your location dictates your lens options. When shooting in confined spaces, your only option may be to use wide lenses, as you may not be physically able to get the camera far enough back to get the framing you want on a longer lens.

Wrapping it up

Some directors don’t think too much about focal length and rely heavily on their cinematographer to make that choice. If the director has a clear vision and can communicate that well, a good cinematographer can interpret his intent and choose lenses that support his vision. Other directors, like Kubrick, Steven Spielberg, or Paul Thomas Anderson are very picky about the lenses they use. Whether you dictate the focal length of every shot, or rely on your cinematographer, it is important to have a functional understanding of that choice and why it matters.

Hopefully this is helpful to that end. Feel free to ask any questions in the comments, as well as point out any of your own observations from the footage.

I plan to do a follow up post on focal length and its relationship to camera/subject movement. In the meantime, as you watch films, take note of the way in which the filmmakers utilize different focal lengths, and how they make you feel. Another great way to learn about focal length and composition is through still photography. With an inexpensive DSLR or old film SLR and a zoom lens or a few primes (i.e. a 35mm, 50mm, and 85mm) you can develop an eye for composition and learn a great deal about photography, and cinematography by extension.

If this is helpful for you in any way, I’d love to hear about it. If you have any suggestions for other topics I could cover in similar manner, let me know and I’ll see if I can make it happen.

Resources

Explore the following resources to learn more about focal length and lenses:

- To download a zip file containing full resolution stills of the images used in the article, click here.

- For a little more detail on the definitions of focal length, angle of view, and field of view, check out this concise article with great diagrams.

- Canon’s focal length comparison tool allows you to compare various focal lengths and their fields-of-view online.

- Shooting on 16mm? A 5D? 2/3″ video? Check out AbelCine’s Field of View Comparator to learn how the effects of focal length translate to different formats.

Now I’ll leave you with a bit of wisdom from Roger Deakins, ASC, BSC. The whole clip is gold, but you can skip to 2:30 to hear him talk specifically about lens choice and focal length.

Roger Deakins, ASC, BSC – take 5 – Cinematographer Style from Film and Digital Times on Vimeo.

The learning never stops,

Colton Davie, Cinematographer

-

You are right abou the 32 being normal. On S35 it is the neutral lens. On full frame still neutral is the 50mm.

-

Important stuff. Thanks, Colton!

-

Superb article Colton. Thanks for sharing.

-

Excellent, excellent. Thank you.

Submit a Comment

Comments